Cyberwars; Algeria v. Morocco

also ft Africa's cable problem and Israel, spyware, and corruption

CybAfriqué is a space for news and analysis on cyber, data, and information security on the African continent.

Hi there, Olatunji Alameen here.

Now and then we stumble on radical and encompassing highlights, and I think this is one of them. Each highlight explores something important and enlightening.

Excited for you to read today’s issue and remember to reply if you have questions or feedback!

HIGHLIGHTS

Cyberwars; Algeria v. Morocco

First, let's talk about cyber wars. Not the Hollywood kind with exploding monitors and neon green code scrolling infinitely while someone yells "I’m in!" No, the real kind. The kind where one country decides it would be useful, or perhaps just amusing, to mess with another country digitally.

The basic idea of cyber warfare (between nations) is pretty straightforward: use digital means to achieve ends that, in a bygone era, would have required spies in trench coats, physical sabotage, or dropping leaflets from planes. The menu generally includes:

1. Spying (Cyber Espionage): This is probably the bulk of it. Hoovering up government secrets, military plans, corporate intellectual property, sensitive emails, you name it. It's like traditional espionage, but instead of microfilm hidden in a fountain pen, it's terabytes siphoned off a poorly secured server. Is this "war"? Traditionally, spying isn't considered an act of war; it's just sort of assumed everyone is doing it all the time. There's a sort of cynical realism here. Countries spy. Water is wet. If you leave your secrets lying around digitally, someone will probably take them. Complaining about it is like complaining about gravity.

2. Breaking Things (Sabotage): This is closer to the Hollywood version, but still less dramatic. Think less "launching the nukes" and more "making the power grid flicker ominously," "messing with the stock market's plumbing," or "bricking industrial control systems so centrifuges spin themselves to death." Stuxnet, the “alleged” US/Israeli worm that took a bite out of Iran's nuclear program around 2010, is the poster child here. It showed you could cause real, physical damage through code. More recently, Russia has been accused of repeatedly targeting Ukrainian infrastructure – power, communications, etc. – often alongside conventional military actions. This is sometimes called "hybrid warfare," which in this context means "war, by/plus hacking."

3. Sowing lies and Confusion (Disinformation/Propaganda): Using bots, fake accounts, hacked media outlets, or deepfakes to spread narratives, influence elections, sow discord, or generally make people distrust whatever they read online. Again, propaganda isn't new, but the internet lets you target it and scale it in terrifyingly efficient ways.

Usually, it's specialized units within a country's military or intelligence services who wage these wars. Think NSA, GCHQ, Unit 8200, various arms of the PLA or GRU. But sometimes, maybe often, it's done through proxies. Governments might fund, direct, or simply turn a blind eye to ostensibly independent "patriotic hackers" or even criminal groups. This provides plausible deniability, a concept beloved by international relations types. "Was it us who unleashed that worm that crippled global shipping for weeks? Heavens no, must have been some rogue cyber-vandals (that we cannot or will not help you arrest and prosecute). Terrible."

This brings us to the case in North Africa.

The Algerian hacking group, “Jabaroot,” claimed responsibility for breaching Morocco's official website for the Ministry of Economic Integration, Small Enterprise, Employment and Skills. The group claims the attack is a retaliation for Morocco’s harassment of official Algerian social media pages.

Since Algeria cut ties with Morocco in 2021, the two countries have managed to avoid armed confrontation despite several incidents that could have led to escalation. The key flashpoint between both countries is the Western Sahara, where Morocco asserts sovereignty, and Algeria backs the pro-independence Polisario Front. Information operations, arms race, and cyber-espionage have reached record highs between both countries.

The economics of cyber warfares are interesting. Setting up a top-tier state cyber warfare capability is expensive – you need skilled people, R&D, infrastructure. But maybe it's cheaper than building another aircraft carrier? And the potential return on investment for stealing, say, the blueprints for a multi-billion dollar fighter jet is pretty good. On the flip side, the victims bear enormous costs – direct financial losses (think ransomware demands, though states might use ransomware more for disruption than cash), recovery expenses, lost productivity, stolen IP value, and the ever-increasing cost of cybersecurity defenses and insurance. Case in point, NotPetya, which was aimed at Ukraine, but ended up going on a global joyride costing companies like Maersk, Merck, and FedEx hundreds of millions collectively.

Morocco's social security agency said a handful of data were stolen from its systems in a cyberattack this week that resulted in personal information being leaked on the messaging app Telegram. Yet, the response has been swift. In a dramatic counterattack, a group of Moroccan hackers infiltrated the systems of Algeria’s Social Security Fund for Postal and Telecommunications Workers (MGPTT), leaking 13 GB of sensitive data—including ID numbers, money transfer orders, and administrative documents.

How legal/ethical is all of this? Everyone sort of agrees that existing international law applies to cyberspace. The UN Charter's prohibitions on the use of force, the principles of sovereignty, the laws of armed conflict (International Humanitarian Law, or IHL) – they don't just stop working because the attack vector involves packets instead of projectiles.

But “how” they apply is… fuzzy.

What counts as a "use of force" or an "armed attack" that justifies self-defense? Is temporarily disabling the power grid equivalent to bombing it? What about stealing all the secrets? What if you just crash their stock market for a day? The Tallinn Manual, an academic project trying to hash this out, suggests cyber operations causing significant physical damage or death probably qualify. Mere annoyance or espionage, probably not. But there's a vast grey area in between.

Africa’s cable problem

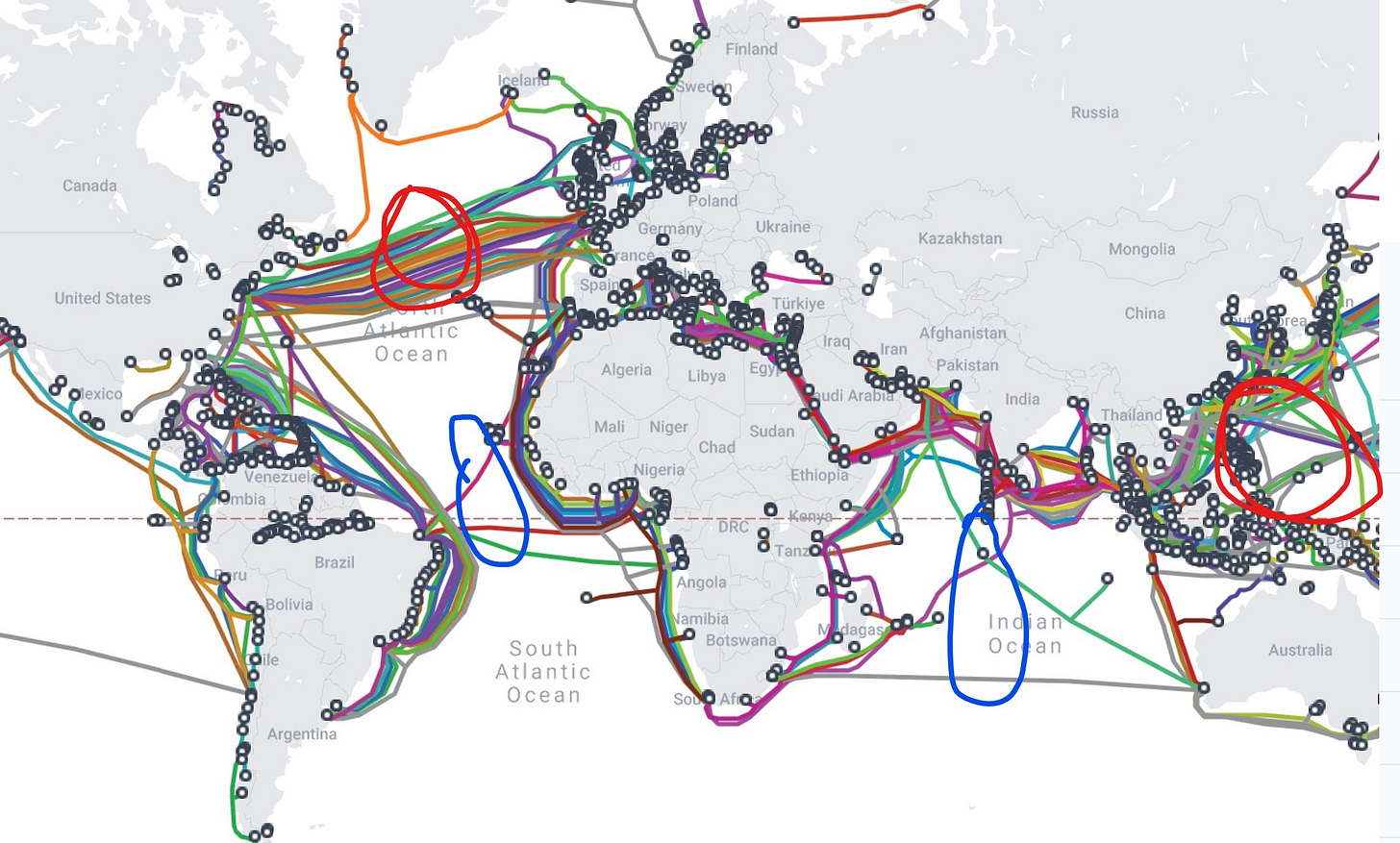

If you’re here, you probably already know that most of the internet is mostly made up of very long, very thin strands of glass bundled into cables lying somewhat precariously on the bottom of the world's oceans. And sometimes, those cables break.

Recently, Liberia had a bit of trouble when the Africa Coast to Europe (ACE) cable, its main internet pipe, reportedly got damaged during some construction work near the shore. If you’ve been following recent cable accidents across the continent, you’re inclined to believe that this is an acutely African problem.

If you're connecting, say, New York and London, there are loads of cables snaking across the Atlantic. If one gets accidentally snagged by a fishing trawler or disturbed by an underwater tremor, the traffic mostly just shrugs, politely asks the other cables to handle the load, and your email still arrives. Maybe things get a tiny bit slower, maybe the network engineers have a 10% more stressful afternoon, but the whole system does not collapse.

Africa, historically, hasn't had that luxury. Fewer cables connect the continent to the rest of the world, and fewer cables interconnect African countries themselves. This means that individual cables often carry a much larger proportion of a country’s, or even a region's, traffic. They become super-critical single points of failure.

We saw this play out spectacularly in March 2024. Not one, not two, but four major cables serving West and Southern Africa went down simultaneously – WACS, ACE, MainOne, and SAT-3. A lot of countries suddenly found their primary internet connections severely degraded or completely severed. Businesses in Nigeria ground to a halt, banks struggled, mobile networks in Ghana went haywire, and South African companies scrambled to reroute what little traffic they could. A few months later, East Africa had its own moment when EASSy and Seacom cables were cut.

It turns out that when your nation relies heavily on one or two main fiber optic arteries, and those arteries run through environments prone to things like shifting seabeds (the March 2024 breaks were suspected to be caused by underwater landslides or currents near Côte d’Ivoire), you're living dangerously.

And the cost isn't trivial. In Nigeria alone, the economic fallout from the March 2024 outage was estimated at a staggering ₦273 billion (around $593.6 million at the time) in just four days. Globally, while hard to aggregate, the costs of disruption are immense.

Fixing these things isn't like patching a pothole. It involves dispatching specialized cable-laying ships (there aren't that many of them), locating the fault kilometers below the ocean surface, grappling the broken ends (which might be buried or separated), hauling them up, painstakingly splicing the hair-thin glass fibers back together in a clean room environment onboard, reinforcing the splice, and carefully lowering it back down. The estimated repair time for the March 2024 breaks was around eight weeks and reports about repair costs threw around figures like a billion dollars – though whether that was for the specific repairs or an estimate for building the new cables needed to prevent this recurring nightmare is a bit murky. Either way, it's eye-wateringly expensive.

This is one reason why companies are racing to build more cables around Africa – like Google's Equiano or Meta's 2Africa project – the continent remains uniquely vulnerable.

Israel, spyware, and corruption

Governments purchase specialized software a lot, but it’s not every time that a government bureau gets allocated $7 million to purchase a “Cyber Defense System.” When that happens, you as the head of said bureau, have to understand that opportunities come but once.

ICYMI, there’s a small drama unfolding in Ghana, involving the former head of the National Signals Bureau, his wife, an Israeli firm called ISC Holdings, and a pile of allegedly misdirected cash. And i,t is a window into a much bigger, murkier world: the still booming global trade in surveillance technology, and Israel's particularly dominant role as a supplier, especially to governments across Africa and beyond.

Governments want to spy. They want to spy on terrorists, they want to spy on criminals, they want to spy on foreign adversaries, and sometimes, allegedly, they want to spy on activists demanding better governance or journalists asking awkward questions. To do this effectively in the digital age, they need sophisticated tools. And a lot of those tools seem to come from Israel.

It's not just Israel, of course. Companies in the US, UK, China, and the EU are also in the game. Reports suggest African governments alone might be spending over a billion dollars collectively on spyware and surveillance kits from various international vendors. But Israeli firms keep popping up. You have ISC Holdings in the Ghana contract kerfuffle. And then there’s the big one: NSO Group.

NSO Group is famous, or infamous, for Pegasus. Investigations revealed Pegasus was licensed to governments worldwide, including reportedly in African nations like Ghana, Morocco, Rwanda, and Togo. The Ghanaian activist group FixtheCountry, for example, alleged its members were illegally monitored by state security using such capabilities.

So why is Israel such a powerhouse in this field? A few factors seem key:

The Military-Industrial-Cyber Complex: Israel has a renowned high-tech sector, heavily seeded by veterans of elite military intelligence units like the famed Unit 8218. These veterans graduate with cutting-edge cyber skills and often start companies, sometimes building tools conceptually similar to those they used or developed in the service. It’s a well-oiled talent pipeline.

Government as Enabler (and Regulator): Here’s the crucial bit. Selling potent spyware like Pegasus isn't like selling refrigerators. It requires an export license from the Israeli Ministry of Defense. This regulation serves multiple purposes. It ostensibly prevents sales to outright enemies, but it also implicitly bestows a government seal of approval on the buyers. More importantly, it turns these sales into tools of diplomacy. Offering (or withholding) access to these powerful surveillance capabilities can be a form of diplomatic leverage, potentially used to build relationships or encourage normalization, as has been suggested regarding sales across Africa from Togo to Morocco. It's cyber-diplomacy via software license.

The "Battle-Tested" Aura: There’s often an implicit (or explicit) marketing angle that this technology works, possibly because it’s been honed in demanding security environments like the Israel-Palestine war. The state of Israel has also been reported to have outrightly test-run its surveillance tech on Palestinian populations.

Demand: Let’s face it, the demand is huge. Governments globally are eager for these capabilities.

The problem is the "dual-use" nature of this tech. Sold to combat terrorism and serious crime, it frequently ends up being credibly accused of targeting dissidents, journalists, and political opponents. This is the core controversy that follows firms like NSO Group around. The tools are powerful, perhaps too powerful and too easily misused once they're out the door, even with government licensing.

And the Ghana situation adds another layer: governance and finance. How are these multi-million dollar contracts for sensitive surveillance tech negotiated? Who provides oversight? When the stated purpose is national security, scrutiny can be limited, potentially creating opportunities for graft, as alleged in the Adu-Boahene case. How much of that reported $1 billion+ spent continent-wide evaporates in similar ways?

Ultimately, the demand for powerful digital surveillance isn't going away. And Israeli firms, deeply integrated with their state's security apparatus and diplomatic goals, are exceptionally well-positioned to meet that demand. It's good business for them, a useful tool for Israeli foreign policy, and a source of immense power for the governments who buy the tech. Whether it’s good for privacy, democracy, or clean government in the purchasing countries is, shall we say, a much more open question.

FEATURES

This article explores disinformation in Zimbabwe and the erosion of faith in the media.

HEADLINES

Cyber criminals bypass code of ethics with concerted attacks on the world's healthcare sector

Justice in Ghana, breaking down ATI barriers, and tackling cyber violence across borders

Tunise Telecom Rolls Out 5G Service for Customers in Tunisia

Online Scam: ANCy Togo Denounces Fake Website Posing as Official Organizationcybersecurity

Youth unemployment, another cyber security challenge for Africa

South African minister accused of bending local laws for Elon Musk’s Starlink

ACROSS THE WORLD

The Story of Terrorgram: How Online Extremism Led to a Slovak Terrorist Attack

Ransomware attack exposes customer data at DBS, Bank of China Singapore

Spanish police arrest six for $20 million AI-powered crypto investment scam

OPPORTUNITIES

Fully funded cybersecurity training for youth in West and Central Africa. Apply here